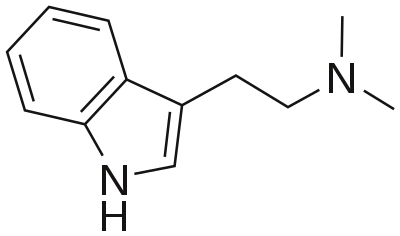

Ayahuasca, also known as the vine of the soul is a sacred medicinal brew that has been consumed for centuries and possibly millennia by the indigenous peoples of the Amazon basin. Ayahuasca is traditionally made by boiling Banisteriopsis caapi vines with leaves from the Psychotria viridis plant. The resulting brew contains the psychoactive molecule DMT (N,N-Dimethyltryptamine). DMT is a tryptamine that occurs naturally in many plants and animals. Scientists have discovered that DMT is endogenously produced in the brains of rats [1]. The consumption of ayahuasca is known to induce altered states of consciousness that shamans and ayahuasca seekers alike value for its ability to potentiate powerful psychotherapeutic healing and evoke realizations that may lead to internal psychological transformations. The power of this psychological healing has been documented in several studies where peer-reviewed research has revealed ayahuasca’s ability to help rehabilitate people suffering from treatment-resistant disorders, including depression and anxiety [2], [3]. Furthermore, studies have shown that ayahuasca has the ability to greatly help people suffering from various forms of addiction, especially alcohol addiction [4], [5]. A 2021 study published in Nature confirmed ayahuasca’s ability to induce personality changes with the most pronounced shift being a reduction in neuroticism [6]. With dozens of studies emerging from the primary literature documenting ayahuasca as a powerful psychotherapeutic medicine capable of potentiating positive life transformations, the time has come to destigmatize ayahuasca and recognize it for what it is — a healing plant medicine.

History & Healing

The history of ayahuasca begins with the Shamans of South America. Shamans are individuals who are skilled in navigating through altered states of consciousness for the purpose of obtaining knowledge that can help to heal themselves, as well as others within the community. Shamans are known to use psychoactive plants as a means to access altered states. The practice of shamanism dates back to pre-colonial times and has been widely practiced throughout the world especially in Europe, Asia, Tibet, North America, South America, and Africa. Evidence of ritualistic ayahuasca use dates back to at least 1,000 years ago [7]. This discovery was made by Melanie Miller, Ph.D., a former UC Berkeley researcher. In 2019, while excavating in South America, Dr. Miller discovered a pouch made from three fox snouts sewn together [8]. The contents of the fox-snout pouch were molecularly identified as 5 different psychoactive substances including cocaine, benzoylecgonine (BZE), harmine, bufotenine, dimethyltryptamine (DMT), and possibly psilocin. In South America, Harmine is most commonly found in the Banisteriopsis caapi vine (one essential ingredient in ayahuasca) and DMT is found in several South American botanicals, however, its highest concentration is in the leaves of the Psychotria viridis. The presence of harmine and DMT in the ancient fox-snout pouch suggests that shamans were aware of the effects that these substances have together as far back as 1,000 years ago and possibly longer.

The idea of using psychoactive substances for spiritual purposes to heal past traumas may seem like a foreign idea to some. However, psychoactive plant medicine has played an integral role in the development of human consciousness for thousands of years. Indigiousnous cultures like the Aztecs, Mazatecs, Mayans, and Incas have regarded sacred plant medicines as religious and spiritual sacraments. These cultures valued psychoactive plants for their abilities to induce powerful inner transformations on the level of mind, body, and soul.

The stigmatization of psychoactive plant medicine has been attributed back to the days of the Spanish conquest. In 1519, Spanish conquistadors began colonizing much of Central and South America. In addition to brutally conquering indigenous land, the Spaniards brought with them clergy members of the Catholic Church whose goal was to impose a kind of “spiritual conquest” upon the indigenous population, meaning forced conversion to Catholicism. The Catholic Church learned about the indigenous peoples’ use of sacred plant medicines and recognized the potential that these substances had to induce altered states of consciousness. This type of cognitive liberty threatened the Church’s ability to control religious expression, spirituality, and individual identity. As a result, the Church declared any use of sacred plant medicine as a form of heresy; and associated the use of psychoactive plants with witchcraft and charlatanism [9]. Anyone caught with plant medicine was met with violent force, often tortured into obedience. The suppression of plant medicine was one of many lasting consequences of the Spanish conquest. This short historical account depicts one of many ways in which sacred plant medicine has been suppressed and stigmatized over the centuries. It goes without saying that there are many other ways that stigmatization has occurred. However, the goal of this article is not to linger on stigmatization from the past, but rather, to present an honest account of the powerful transformative healing potentials that plant medicine, specifically, ayahuasca can induce.

It is important to recognize that ayahuasca may aid in an individual seeking a psychological healing transformation, however, plant medicine is not always necessary for this process to unfold. True healing requires a commitment to improving oneself through practices of self-love. In the case of someone who seeks ayahuasca for the purposes of healing, it essential to realize that the healing process is ongoing and beings weeks or months prior to the actual ayahuasca ceremony. The lessons learned in ceremonies often take months or years to be fully understood and integrated. The ceremony itself is but a small part of the healing process — it is nothing but a reminder of who we truly are —unique individual expressions of a greater collective consciousness, voluntarily constrained by the physical boundaries of time and space — existing in this world for the purpose of rediscovering who we truly are — all the while playing a game we call life on earth.

Dieta

In an effort to prepare the body for the healing potentials that ayahuasca can yield, it is common practice to go on a diet or “dieta” for 2 weeks to 1 month prior to consuming ayahuasca. The purpose of this dieta is to cleanse the body of toxins and impurities so as to prepare the body for the medicine. During a dieta, it is common for people to abstain from recreational drugs, salt, sugar, oil, caffeine, dairy, spicy foods, processed foods, pork & red meat, and any form of sexual activity. Following this dieta lays the groundwork for the experience and also demonstrates deep respect and commitment to the healing process. The biological mechanisms behind ayahuasca-induced psychological healing are fascinating and have only recently been reported. Let us now turn our attention to how exactly this healing takes place from a biological level of analysis.

Ayahuasca In the Brain

The primary psychoactive agent in ayahuasca is DMT — a serotonergic analog with an affinity for Serotonin 2A (5-HT2A) receptors in the brain [10]. Most classic psychedelics also target 5-HT2A receptors which begs the question, what are these receptors responsible for? According to neuroscience researchers Ari Brouwer and Robin Carhart-Harris, the 5-HT2A receptor is “a key trigger site for inducing pivotal mental states” [11]. These mental states are typically induced by things that cause extreme biological stress like fasting, isolation, cold exposure, breathing exercises, and sometimes psychedelics. A pivotal mental state could be defined as “a hyper-plastic state aiding rapid and deep learning that can mediate psychological transformation” [11]. It comes as no surprise that the receptors that are targeted by classic serotoninergic psychedelics in the brain are the same receptors responsible for mediating psychological transformations.

Although many psychedelics target these receptors, ayahuasca is unique because its active ingredient DMT is the most powerful psychoactive molecule known at this time. It turns out that the DMT contained in the leaves of the Psychotria viridis (and other DMT-containing plants) is not psychoactive if orally consumed. Rather, it needs to be coupled with a monoamine oxidase inhibitor (MAOI) in order for the psychedelic effects to manifest. This is because monoamine oxidase enzymes in the stomach break down DMT through a process known as oxidative deamination, rendering the DMT inactive before it is able to enter the bloodstream [12]. This is where the vine of the Banisteriopsis caapi comes in, once macerated and boiled, the vine releases three harmala alkaloids — Harmine, Harmaline, and Tetrahydroharmine. These β-carboline class indole alkaloids act as monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs)[13]. Suppression of MAO enzymes prevents the deamination of DMT, allotting higher levels of bioavailability; thus allowing DMT to enter the bloodstream and travel up to the brain. DMT has the ability to cross the blood-brain barrier through active transport across the endothelial plasma membrane [12].

Once in the brain, the DMT is able to quickly find receptors where it can latch onto and agonize. The primary receptors of interest (5-HT2A receptors) are G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) with Gq subunits [14], [15]. When a ligand binds to these GPCRs, the Gq subunits activate intracellular signaling cascades that lead to the upregulation of specific kinases called Protein Kinase C (PKC). Inside the cell, PKC phosphorylates other proteins which have a wide array of effects ranging from increasing Long-Term Potentiation (LTP) to the regulation of certain transcription factors [16], [17]. These intracellular signaling cascades are believed to be cellular mechanisms responsible for the radical shift in consciousness brought about by DMT. Scientists have a neurobiological understanding of the cellular and molecular mechanisms that induce the shift in consciousness brought about by DMT. However, the subjective “mind-manifesting” nature of the ayahuasca experience is not yet fully understood.

How We Got Here & Legality

In the mid-twentieth century, ayahuasca became known to the Western world around the same time as the emergence of New Age culture. Ayahuasca has been popularized through its appearance in documentaries on mainstream networks like National Geographic, Discovery, and BBC. Articles in popular magazines and blogs have also brought public awareness to the sacred Amazonian brew. Additionally, there have been strong research interests within the scientific community to better understand ayahuasca’s neurobiological mechanisms. All of these factors have paved the way for the creation of so-called “Ayahuasca Tourism” [18]. This global tourism associated with ayahuasca has brought money into many Central and South American countries at the price of increased harvesting of the natural resources required for the creation of the brew. As a result, there have been negative environmental effects as supply is decreasing while demand is increasing. Ayahuasca tourism has raised spiritual, ethical, and ecological concerns.

In the United States, the plants used to create ayahuasca (i.e., Banisteriopsis Caapi and Psychotria viridis) are legal. However, the DMT created from the brew is illegal and is considered a Schedule I substance under the Controlled Substances Act of 1970 [19]. In several Central and South American countries like Costa Rica, Brazil, and Peru ayahuasca and DMT are legal. Interestingly, DMT is also legal in Italy and is legal for research purposes in Spain and Romania [20].

Concluding Thoughts

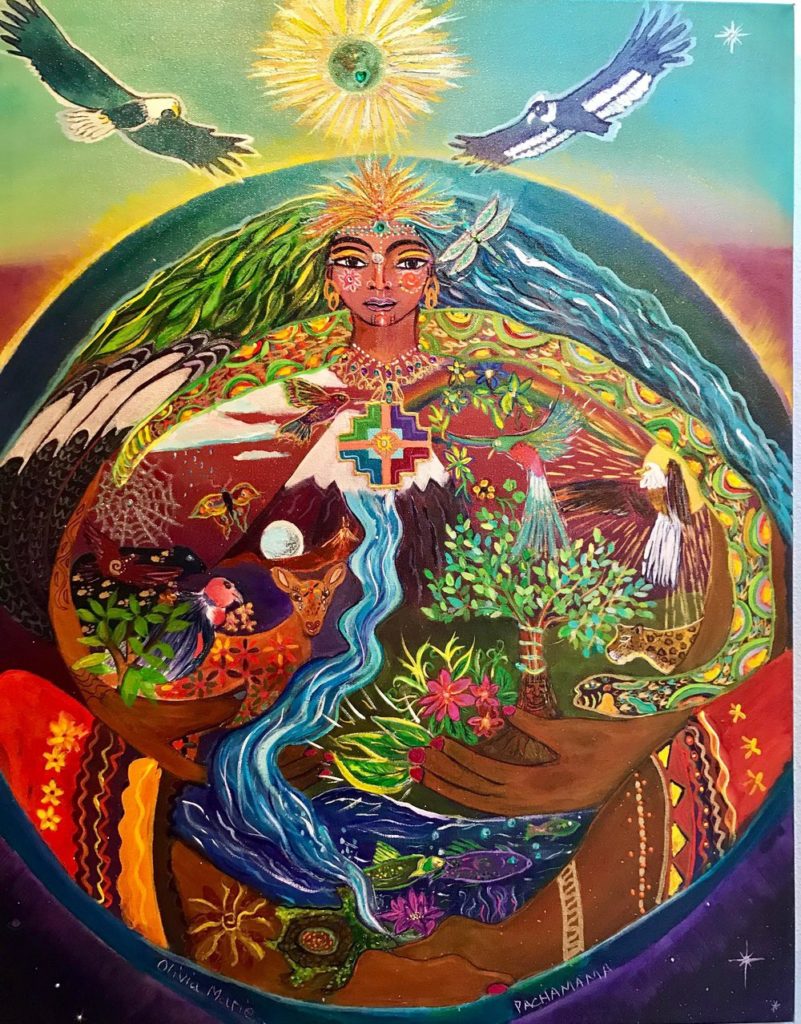

For those who seek it, ayahuasca may provide an opportunity to confront unresolved past traumas, reconnect with Source, and gain insights into what we call consciousness. In an ayahuasca ceremony, it is not uncommon to come into contact with the primordial Mother — Mother Ayahuasca. The spirit of Mother Ayahuasca is an archetypal expression of the divine feminine. But she is much more than that. The indigenous peoples of the Andes refer to Mother Earth as Pachamama. Pachamama is a beautiful Goddess who represents nature and the spirit of the planet. She is a spirit comprised of nature — often depicted as emerging from a tree, mountain, or river. It seems as though the spirit of Mother Ayahuasca is the same spirit embodied in Pachamama. Pachamama could be understood through a Jungian viewpoint as similar to the ouroboros, which depicts a dragon eating its own tail, symbolizing the infinite cycle of life, death, and rebirth. Pachamama is an embodiment of the ouroboros in the way that she too is an infinite symbol of life, death, and rebirth. Mother Ayahuasca is known to be a healer and often the spirit guide who helps to facilitate psychological healing and inner transformations.

In the West, we are skeptical of anything that does not fit within our contemporary scientific, materialist, reductionist framework. As a result, we lose our connection with phenomena that occur outside of this framework. Shamanism is one example of a practice that does not appeal to the Western model of psychological healing. Yet, there are countless examples of shamanic plant medicine ceremonies that have led to deep psychological healing and inner transformations in individuals suffering from treatment-resistant disorders. We cannot explain the nature of these shamanic experiences within our Western models. Therefore, it seems as though a paradigm shift is on the horizon —this shift will have to account for the questions raised by such experiences. Is the observable world all there is? Is it possible there is another dimension existing concurrently with our own? Are there benevolent ancestral spirits living amongst us? Is there an all-knowing and all-intelligent Source from which life emerged? The answers to these questions will vary depending on who you ask. However, I tend to believe that the duality created between conflicting viewpoints cannot sustain forever. At some point, we will have to come together; shamans and scientists alike and discuss, explore, and ultimately seek to understand the nature of the psychedelic experience.

Ayahuasca is a tool that enables us to better understand the nature of our existence and the consciousness of our planet. It is a healing medicine with the potential to give individuals an opportunity to see themselves and the world from different perspectives. Often allowing individuals to psychologically return to and confront traumatic experiences — be they first-hand or genetically encoded. Amidst the inevitable skepticism surrounding plant medicine and other non-Western healing practices, one thing is certain – our world is suffering. Poverty, abuse, terrorism, pollution, and many other horrors plague our world. The solution, as far as I can tell, is to strive to become the greatest possible version of ourselves, so that we can maximize our chances of helping to heal the world. We have the potential to leave this world in a better condition than it was when we entered it. In order to make this vision a reality, we will need all the help we can get to heal both ourselves and our planet. Ayahuasca has demonstrated itself to be an alley in this healing journey. The time has come to recognize, destigmatize, and accept ayahuasca for what it is — powerful healing medicine.

References

[1]. Dean, J. G., Liu, T., Huff, S., Sheler, B., Barker, S. A., Strassman, R. J., . . . Borjigin, J. (2019). Biosynthesis and Extracellular concentrations OF N,n-dimethyltryptamine (DMT) in mammalian brain. Scientific Reports, 9(1). doi:10.1038/s41598–019–45812-w

[2]. Palhano-Fontes, F., Barreto, D., Onias, H., Andrade, K. C., Novaes, M. M., Pessoa, J. A., . . . Araújo, D. B. (2018). Rapid antidepressant effects of the psychedelic ayahuasca in treatment-resistant depression: A randomized placebo-controlled trial. Psychological Medicine, 49(4), 655–663. doi:10.1017/s0033291718001356

[3]. Galvão, A. C., De Almeida, R. N., Silva, E. A., Freire, F. A., Palhano-Fontes, F., Onias, H., . . . Galvão-Coelho, N. L. (2018). Cortisol modulation by ayahuasca in patients with treatment resistant depression and healthy controls. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 9. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00185

[4]. Lawn, W., Hallak, J. E., Crippa, J. A., Dos Santos, R., Porffy, L., Barratt, M. J., . . . Morgan, C. J. (2018). Author Correction: Well-being, problematic alcohol consumption and Acute SUBJECTIVE drug effects in PAST-YEAR ayahuasca users: A Large, international, self-selecting online survey. Scientific Reports, 8(1). doi:10.1038/s41598–018–21666–6

[5]. Talin, P., & Sanabria, E. (2019). Ethnographic study: Ayahuasca’s entwined efficacy: An ethnographic study of ritual healing from “addiction” 1. Proposing Empirical Research, 182–187. doi:10.4324/9780429463013–71

[6]. Weiss, B., Miller, J., Carter, N., & Campbell, W. K. (2020). Examining changes in personality following shamanic ceremonial use of ayahuasca. Nature Scientific Reports. doi:10.21203/rs.3.rs-111130/v1

[7]. Blakemore, E. (2021, February 10). Ancient Ayahuasca found IN 1,000-year-old Shamanic pouch. Retrieved April 11, 2021, from https://www.nationalgeographic.com/culture/article/ancient-hallucinogens-oldest-ayahuasca-found-shaman-pouch

[8]. Miller, M. J., Albarracin-Jordan, J., Moore, C., & Capriles, J. M. (2019). Chemical evidence for the use of Multiple PSYCHOTROPIC plants in A 1,000-year-old RITUAL bundle from South America. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 116(23), 11207–11212. doi:10.1073/pnas.1902174116

[9]. Carod-Artal, F. (2015). Hallucinogenic drugs in pre-columbian Mesoamerican cultures. Neurología (English Edition), 30(1), 42–49. doi:10.1016/j.nrleng.2011.07.010

[10]. Barker, S. A. (2018). N, N-Dimethyltryptamine (dmt), an Endogenous Hallucinogen: Past, present, and future research to determine its role and function. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 12. doi:10.3389/fnins.2018.00536

[11]. Brouwer, A., & Carhart-Harris, R. L. (2020). Pivotal mental states. Journal of Psychopharmacology, 026988112095963. doi:10.1177/0269881120959637

[12]. Carbonaro, T. M., & Gatch, M. B. (2016). Neuropharmacology of N,N-DIMETHYLTRYPTAMINE. Brain Research Bulletin, 126, 74–88. doi:10.1016/j.brainresbull.2016.04.016

[13]. Morales-García, J. A., De la Fuente Revenga, M., Alonso-Gil, S., Rodríguez-Franco, M. I., Feilding, A., Perez-Castillo, A., & Riba, J. (2017). The alkaloids of banisteriopsis caapi, the plant source of the Amazonian hallucinogen Ayahuasca, Stimulate adult neurogenesis in vitro. Scientific Reports, 7(1). doi:10.1038/s41598–017–05407–9

[14]. Serotonin 2A (5-HT2A) Receptor FUNCTION: Ligand-dependent mechanisms and pathways. (2007). Serotonin Receptors in Neurobiology, 123–150. doi:10.1201/9781420005752–11

[15]. Johnson-Farley, N. N., Kertesy, S. B., Dubyak, G. R., & Cowen, D. S. (2005). Enhanced activation Of AKT And EXTRACELLULAR-REGULATED kinase pathways by Simultaneous occupancy of GQ-COUPLED 5-ht2a receptors And Gs-coupled 5-HT7A receptors in Pc12 cells. Journal of Neurochemistry, 92(1), 72–82. doi:10.1111/j.1471–4159.2004.02832.x

[16]. Linden, D. J., & Routtenberg, A. (1989). The role of protein kinase c in long-term potentiation: A testable model. Brain Research Reviews, 14(3), 279–296. doi:10.1016/0165–0173(89)90004–0

[17]. Anji, A., Hanley, N. R., Kumari, M., & Hensler, J. G. (2001). The role of protein kinase c in the regulation of serotonin-2a receptor expression. Journal of Neurochemistry, 77(2), 589–597. doi:10.1046/j.1471–4159.2001.00261.x

[18]. Gurvičius, T. (n.d.). The Implications of Ayahuasca Tourism on the Sustainable Development of Peru.

[19]. Controlled Substances Act, 1249 § Public Law 91–513 (1970).

[20]. Legal status of ayahuasca by country. (2021, March 23). Retrieved April 11, 2021, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Legal_status_of_ayahuasca_by_country

[21]. DMT Quest. (2021, January 25). DMT Quest Documentary [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=My95s6ZryPg

[22]. Strassman, R. (2001). DMT: The spirit molecule. Rochester, VT: Park Street Press.

About the article

This article was written during my senior year at UC Berkeley while studying Cognitive Science and Neurobiology. At the time of this publication, I have been co-leading the Publications department at Neurotech@Berkeley and serving as a facilitator for the Introduction to Psychedelic Science class offered at UC Berkeley. As we move into a brighter tomorrow, I hope this article serves to educate, inspire, and drive people to develop a greater appreciation and respect for plants and their mystical qualities.

— Oliver Krentzman